THE

BLACK POWDER WARTHOG

Another version of this essay appeared in Magnum Magazine in South Africa

After a year of planning and anticipation (and a 40-hour one-way transit via Germany!) I arrived in Namibia for a plains game hunt with CEC Safaris, a small but very fine hunting company located in the Omitara district about 120 kilometers east of Windhoek. My principal quarry was an eland (and boy, did I get one...watch this space!) but another of my goals for this trip was to hunt in Africa with a muzzle-loading rifle. After 20+ years’ experience as a muzzle-loader hunter in North America, it was time to try it abroad.

In the past 40 years shooting and hunting with black

powder rifles in the US has evolved from the curious hobby of a small coterie

of devotees in funny clothes to a sizable industry. Muzzle-loaders are today used on every type

of game in North America, the number of hunters choosing them increasing every

season.

In the past 40 years shooting and hunting with black

powder rifles in the US has evolved from the curious hobby of a small coterie

of devotees in funny clothes to a sizable industry. Muzzle-loaders are today used on every type

of game in North America, the number of hunters choosing them increasing every

season.

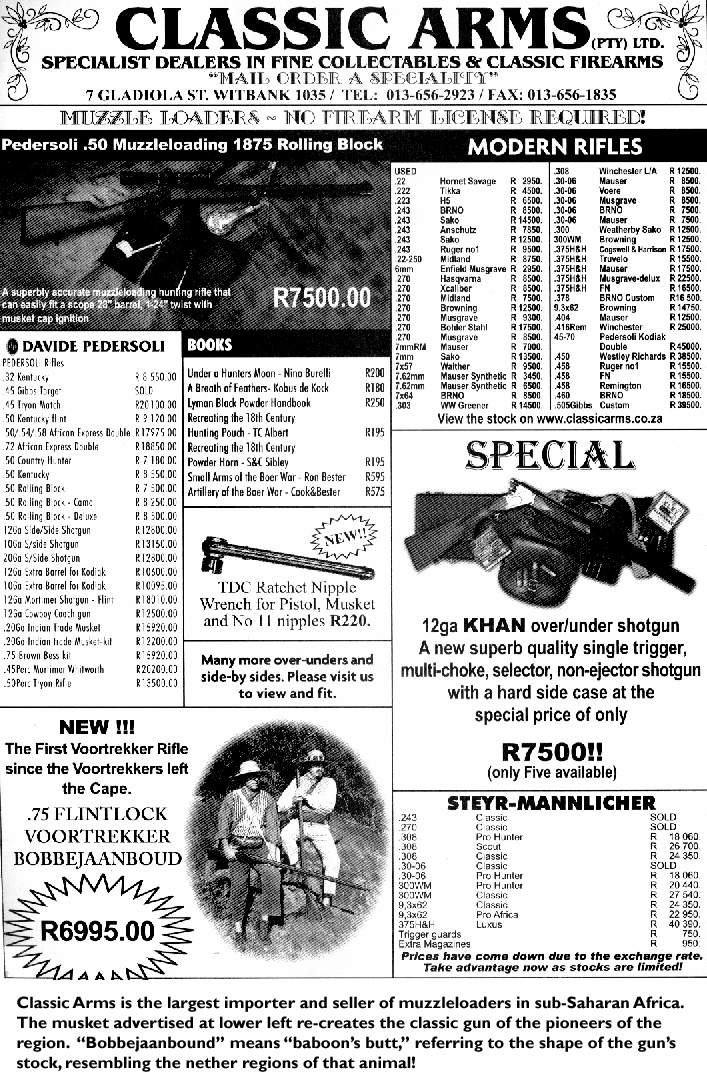

With the passage of its new Firearms Control Act a few years ago, South Africa very sensibly eliminated the requirement to obtain a license for “traditional” style (i.e., sidelock) muzzle-loading rifles (in-lines and muzzle-loading handguns remained regulated). As a result, traditional style rifles are now even more popular and are seeing more widespread use in hunting and target shooting in Africa, as they have here in the USA.

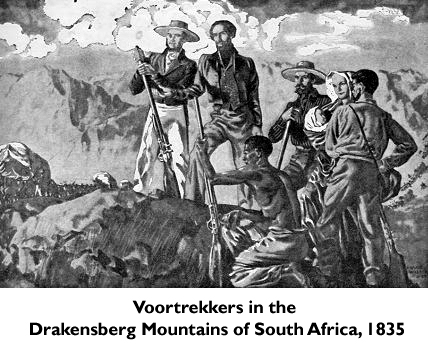

And just as in North America, muzzle-loading rifles were

essential to the exploration and settlement of Africa. The intrepid people who landed at the Cape

and their descendants who pushed into the interior regions carried first

flintlock and later percussion-ignition muzzle-loading rifles to protect

themselves against hostiles and predators, and to feed their families. When efficient breech loading rifles became

common in the late 19th Century, use of the older technology

diminished but it never quite died out on either continent. The celebration of the American Civil War

Centennial (1960-65) saw a resurgence of interest in muzzle-loading guns, which

has since spread worldwide. The demand

has fueled the growth of a sizable industry making replica guns in Europe (chiefly in Italy and Spain); it’s

probable that more such rifles are being made today than in their heyday in the mid 19th Century!

And just as in North America, muzzle-loading rifles were

essential to the exploration and settlement of Africa. The intrepid people who landed at the Cape

and their descendants who pushed into the interior regions carried first

flintlock and later percussion-ignition muzzle-loading rifles to protect

themselves against hostiles and predators, and to feed their families. When efficient breech loading rifles became

common in the late 19th Century, use of the older technology

diminished but it never quite died out on either continent. The celebration of the American Civil War

Centennial (1960-65) saw a resurgence of interest in muzzle-loading guns, which

has since spread worldwide. The demand

has fueled the growth of a sizable industry making replica guns in Europe (chiefly in Italy and Spain); it’s

probable that more such rifles are being made today than in their heyday in the mid 19th Century!

Similarly, the manufacture of black powder never really ended. It is still made in the USA, in Europe, and in South America. In the USA "replica" powders offering similar performance but easier clean-up and safer shipping came into common use about 20 years ago. Thanks to the de-licensing of muzzle-loaders, a company in South Africa is now manufacturing a home-grown "replica" powder called "Sannadex," to serve the needs of the growing numbers of BP hunters. In time this will no doubt be available in other countries of the region.

Similarly, the manufacture of black powder never really ended. It is still made in the USA, in Europe, and in South America. In the USA "replica" powders offering similar performance but easier clean-up and safer shipping came into common use about 20 years ago. Thanks to the de-licensing of muzzle-loaders, a company in South Africa is now manufacturing a home-grown "replica" powder called "Sannadex," to serve the needs of the growing numbers of BP hunters. In time this will no doubt be available in other countries of the region.

Using a muzzle-loader safely and effectively requires paying a lot of attention to detail, much more so than is true with breech-loading guns. Most importantly, you must have the right mindset. Shooting a muzzle-loader is a slow and deliberate process: you have to think about what you're doing until it becomes habit. Anyone who hunts with one has to become thoroughly familiar with its idiosyncrasies, to know what it will (and won’t) do under every circumstance; and to accept a misfire or hangfire philosophically when it happens (as it inevitably will). But once the drawbacks of these rifles are understood and accepted, using one makes you a better hunter. Knowing that you have only one shot (or at most two) compels you to acquire patience, good fire discipline, and a willingness to try to get closer to your game.

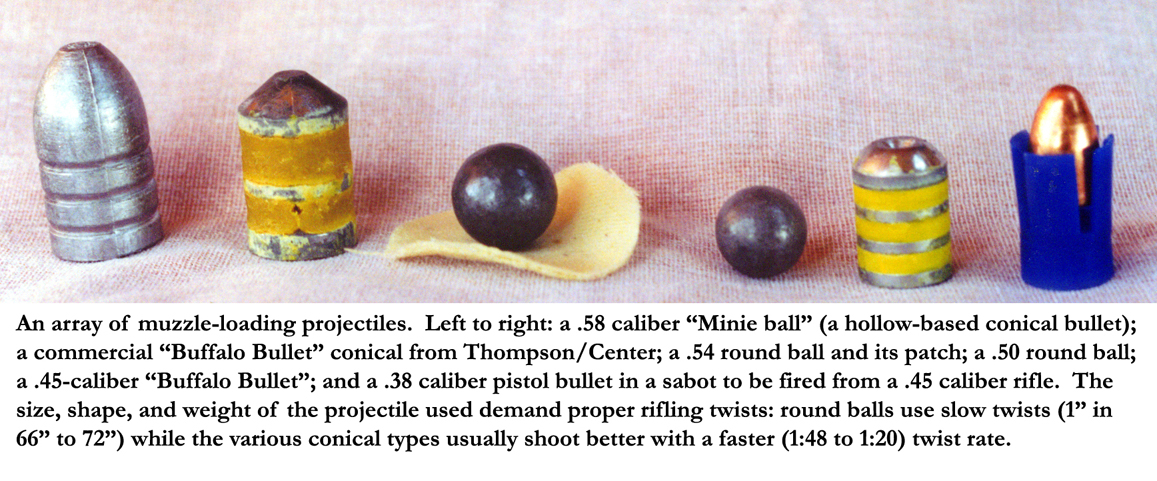

Muzzle-loading rifles don’t give up anything in terms of effectiveness on game. The hunter who understands and respects their limitations will find he's not seriously handicapped. They may be technologically obsolete, but they’re "real guns” by any definition, far better killers than someone who's never used one might think. The principal factor limiting their performance is practically-attainable muzzle velocity. A muzzle-loader is doing very well to manage 1800 fps because black powder and the replica powders simply can't generate the pressures smokeless powder can. The key to effectiveness is the bullet, and the formula is very simple: the heavier the bullet, the more effective the rifle will be.

Despite modest "paper" ballistics, most muzzle-loading rifles use bullets that are quite a bit heavier than those used in common centerfire hunting guns. The weight translates to high proejctile momentum, a measure at least as important as nominal energy level. Furthermore, muzzle-loader bullets rarely if ever break up on impact. Momentum coupled with the molecular cohesiveness of lead give them astonishing penetration.It’s rare to recover a bullet when used on an appropriately sized animal: normally they go straight through and exit (as a bullet should) intersecting vital structures along the way.

Nor do these these large projectiles produce masses of blood-shot meat: the old saying that “you can eat right up to the edge of hole" is pretty much the case. The typical permanent wound channel will be slightly larger than bullet diameter, quite big enough to be quickly fatal when using a bullet 12mm or more in diameter. Increasing projectile weight and diameter increases effectiveness, and for larger animals the practice is to move up to a larger caliber.

In North America where the usual quarry is the whitetailed deer, .50 caliber rifles rule the roost, but for the larger and tougher game of Africa something bigger is indicated: a .54 or .58, or even a .72. The late Val Forgett, founder of Navy Arms and one of the founders of the replica muzzle-loading rifle industry, used a .58-caliber Hawken to take Cape Buffalo and other dangerous game. Needless to say, effectiveness is enhanced by proper placement.

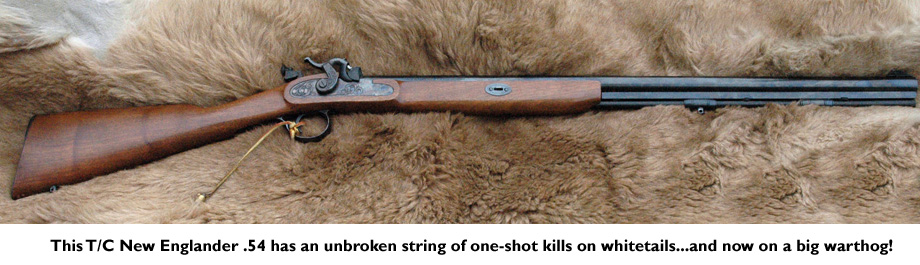

For my hunt, along with a centerfire rifle I opted for my tried-and-true Thompson/Center .54, a rifle that’s served me well. A .54 is regarded as pretty heavy metal in North America, suitable for game up to and including elk. In Africa I’d trust it on any antelope smaller than an eland. If I could stalk close enough I’d have no hesitation using it on a wildebeest or a zebra.

For the visiting hunter, bringing a muzzle-loader does present some logistical problems. You can’t bring gunpowder or

percussion caps on airplanes, so I brought the rifle and the bullets, and asked

CEC to buy me some caps and powder in Windhoek. The selection was limited to what the dealer could

get—no special orders!—and turned out not to include the brand of powder I

normally use. A visitor can expect to

play around with the load he uses a bit at the range before setting out into

the field: not all black powder generates the same power, and 90 grains of

Powder X may well give you a different impact point than the same charge of

Powder Y.

For the visiting hunter, bringing a muzzle-loader does present some logistical problems. You can’t bring gunpowder or

percussion caps on airplanes, so I brought the rifle and the bullets, and asked

CEC to buy me some caps and powder in Windhoek. The selection was limited to what the dealer could

get—no special orders!—and turned out not to include the brand of powder I

normally use. A visitor can expect to

play around with the load he uses a bit at the range before setting out into

the field: not all black powder generates the same power, and 90 grains of

Powder X may well give you a different impact point than the same charge of

Powder Y.

Luckily the shop in Windhoek carried WANO, a good quality powder made in Germany, and American-made CCI caps with which I was familiar. Although the price was four times what it would have cost in the USA—$85 for a pound of powder!—set in the context of the total cost of the hunt this wasn’t all that much.

My rifle also produced some amusing moments at the Firearms Check Counter in the airport in Windhoek. Entry into Namibia with guns is a routine matter, and the Namibian Police (unlike the South African Police) make it as painless as possible. I was met by a very polite and cheerful officer who examined the rifle and asked about the “cartridges” for it. He hadn’t a clue what a “muzzle-loader” was and couldn’t comprehend the idea that there weren’t any “cartridges.” All he knew was that he was supposed to get a count of the number I was bringing in. In the end I simply told him how many “bullets” I had, and that satisfied him. Upon leaving, a different officer—equally polite and helpful and equally ignorant of the nature of the rifle—also asked about how many “cartridges” I had used: I told her how many “bullets” I’d used, and that was that!

The Luggage Gorillas employed by one of the airlines managed to damage the rear sight on my rifle. They must have worked pretty hard at that: my rifle case is made with welded and riveted corners and is supposed to protect the guns come what may. But when Cornie Coetzee, my PH, picked up the rifle to inspect it, and tried to look through the peep sight, he discovered that it had been bent to the point where you couldn’t see through it!

Luckily he’s a gunsmith as well as a PH. He removed the sight and took it into his shop, where he re-bent it to the correct angle; we sighted the gun in, and all went well afterwards. His skill saved this portion of my safari.

Black powder produces a very impressive fireball when the gun is shot. Cornie was concerned that it might start a grass fire, and from the image at left you can perhaps understand why! But I assured him that our Autumn woods are every bit as dry as the winter veldt and I had yet to start a fire there, nor had I ever heard of such a happening in modern times. I use properly-lubricated cotton patches and wool over-powder wads that won’t ignite, so there was no danger.

I chose to use my .54 on a warthog. I’d seen warthogs many times but never hunted them. As everyone knows, they’re every bit as ugly as…well, warthogs; and although they’re very nearsighted, they have sharp ears and a terrific sense of smell. They also have a reputation for ferocity, but the one I shot never got a chance to display it. As we were driving out into the veldt, France, the tracker (shown below right) spotted a warthog sleeping in the knee-high grass. Cornie wanted me to try stalking it, so we dismounted, I capped my gun, and off we went upwind. By that time I’d been on a few stalks with Cornie—who is a real pro—and I was definitely getting better at the business, though I have to admit I didn’t actually see the pig until he started to move.

He

got up from his bed and started to trot from my left to my right, about 35

yards away. Once I had him in full view, I fired. The bullet took him on his right side behind the shoulder, angling

down, and came out his left shoulder. He

kept moving briefly and disappeared in the grass, leaving a massive blood

trail, spraying the waist high grass as he ran, then keeling over dead within a

few yards of the spot where he’d lain.

He

got up from his bed and started to trot from my left to my right, about 35

yards away. Once I had him in full view, I fired. The bullet took him on his right side behind the shoulder, angling

down, and came out his left shoulder. He

kept moving briefly and disappeared in the grass, leaving a massive blood

trail, spraying the waist high grass as he ran, then keeling over dead within a

few yards of the spot where he’d lain.

This kill was a classic example of how you don’t need high velocity. I was using T/C's 435-grain cylindrical "Maxi-Hunter" bullet, with 90 grains of powder under it. It was moving at a very leisurely pace, perhaps 1200 feet per second. To a person used to a high-velocity rifle, this doesn’t sound very impressive, but that big bullet more or less punched a core out of that warthog that was at least 14mm in diameter. I never recovered it, needless to say, nor did I expect to do so. Those big bullets always pass all the way through any animal that size.

He was a very old boar, perhaps 11 to 12 years old, and even though his tusks were worn and one was broken off from fighting, they were very nice. Cornie was of the opinion that he’d not have made it through another year, so in addition to being a very good trophy, as an animal well past his prime he was a good choice. I asked why the pig let us get so close. “Well,” Cornie replied, “this guy was very old, and he probably had lost some or all of his hearing; and he was likely almost blind.” I wasn’t sure what to think about that answer! It would appear that the only warthog I could stalk was a decrepit Senior Citizen who was both blind and deaf! But he was a fine trophy, any way I looked at it—using the SCI standard he measured a total of 62 cm—and I was satisfied. The Old Piggie went to market on the back of Cornie’s hunting vehicle, and his tusks will eventually decorate my office wall.

All hunts provide excitement. But a hunter who’s beginning to think it’s “too easy” using a modern weapon ought to think about trying it “the hard way,” if only as part of a bigger hunting trip. It’s an easy way to add another dimension of challenge, and to re-connect with the pioneers and hunters of old.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |